Although my ancestors are from Asia Minor, the geography that has been identified as the Heartland of Byzantium, and I spent most of my life in its capital city, Istanbul (Constantinople) where the biggest monument to this once great empire, the Hagia Sophia, is part of the backdrop of everyday life, there was something I always found a little elusive in deciphering the Byzantine civilization and culture. Considering Byzantium was actually an extension of the Greco-Roman culture which happens to form the foundations of the predominant culture in the West today, it is actually quite surprising how little is clearly known of this once central power of late antiquity and early middle ages, especially in contrast to the obsession we seem to possess for the culture of ancient Greece and Rome. Thanks to the enlightening exhibition going on at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that is due to close on July 8th, I feel I have finally found some of the clues to these curious concepts.

|

| Byzantine Empire 550 |

|

| Byzantine Empire 867 |

Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition is an exhibition that brings out the visual manifestations of the transition of power and influence from Byzantine to Islamic rule in the vast areas surrounding the Eastern Mediterranean region which extended from Syria to Egypt and across North Africa from 7th to 9th century. 1 The exhibit highlights the amalgamation of cultures and the coexistence of the different religious communities including Orthodox, Syriac and Coptic Christians as well as members of the Jewish and Islamic communities in the same geography which was known as Byzantium's Southern Provinces.

It is truly fascinating to follow the continuation of certain motifs,like the vine scroll associated with Dionysos, from the Greco-Roman culture make its way to become one of the main components of the visual language of Islamic culture or to observe the cultural continuity on coinage that slowly transforms Byzantine Christian imagery to Arab-Byzantine motifs containing the image of the Caliph instead of the Emperor accompanied with Arabic inscription before banishing images completely. From the mosaics that include both Arabic and Greek inscriptions to wall hangings depicting figures in Roman type tunics side by side with figures wearing dresses reminiscent of Sasanian style riding costumes, the coexistence of the different communities and the intermingling of the various cultures becomes the easily discernible, consistent message of this exhibition.

Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition is organized under thirteen themes that displays works from the different religious communities as well as the situations where vivid proof of the overlap of traditions is present. There is an audio guide for the exhibition that enhances the experience to unparalleled depths. On many of the artifacts there are inscriptions in two, sometimes three languages and these are narrated by native speakers on the audio guide, contributing significantly to the drama of the whole experience. The museum's website has detailed information, including photographs of Selected Artworks. There is also a catalog for this exhibition that I will be reviewing in the near future. I would like to provide a visual tour of the exhibit here using the images and the gallery labels from the Metropolitan Museum's website to point out the artifacts I found especially relevant. Included will be some of my own observations and notes.

Byzantium's Southern Provinces

The first object that greets visitors upon entering the exhibit is the floor mosaic excavated from the Church of Saints Peter & Paul in Gerasa with an inscription that is narrated in both Greek and English on the audio guide. The Met's description is as follows:

|

| Floor Mosaic Depicting the Cities of Memphis and Alexandria, ca. 540 Made in Jordan, excavated Church of Saints Peter & Paul, Gerasa (Yale University Art Gallery) |

"This mosaic from a church floor in the affluent city of Gerasa (modern Jerash) depicts two major Egyptian cities identified in Greek as Alexandria (left) and Memphis (right), sites on the trade routes that made the Byzantine Empire's southern provinces wealthy. The inscription identifies the donor as "my bishop... Anastosios" and describes the church as "adorned... with silver and beautifully colored stones." The motifs -cityscapes, trees, vase with vines, and inscription-were popular throughout the Byzantine Empire and transitioned into the arts of the emerging Islamic world."

With this mosaic, the visitor enters a gallery that sets the stage for the different visual elements in various media that seems to have transferred from classical antiquity to Christian and then to Islamic traditions. Another interesting fact to note is the use of Greek as the language of culture and learning in the Eastern Mediterranean as opposed to Latin which was the official language of Byzantine empire.

|

| Drawing of Job and His Family Represented as Heraclius and His Family 5th century (text), ca. 615-629 (drawing) Made in Egypt |

|

| Plate with the Battle of David and Goliath 629-630 Byzantine Made in Constantinople |

|

| Ewer with Dancing Female Figures within Arcades ca. 6th-7th century Sasanian |

|

| David Appears before Saul |

|

| Saul Arms David |

|

| Samuel Anoints David |

"In 628-629 the Byzantine emperor Herakleios (r. 610-41) successfully ended a long, costly war with Persia and regained Jerusalem, Egypt, and other Byzantine territory. Silver stamps dating to 613-29/30 on the reverse of these masterpieces place their manufacture in Heraklios's reign. The biblical figures on the plates wear the costume of the early Byzantine court, suggesting to the viewer that, like Saul and David, the Byzantine emperor was a ruler chosen by God. Elaborate dishes used for display at banquets were common in the late Roman and early Byzantine world; generally decorated with classical themes, these objects conveyed wealth, social status, and learning. This set of silver plates may be the earliest surviving example of the use of biblical scenes fro such displays. Their intended arrangement may have closely followed the biblical order of the events, and their display may have conformed to the shape of a Christogram, or monogram for the name of Christ..."These solid silver plates made in Constantinople with Scenes from the Life of David are magnificent examples of what we can garner in respect to the visual vocabulary of ancient civilizations. The attention given to the intricate details throughout the plates, the different physiognomies (see: Samuel Anoints David), costumes (see: David Appears before Saul), and textures (see: Saul Arms David) as well as the naturalistic representation of the flowing drapery of the figures are breathtaking. These plates alone are worthy of a trip to the Met - if not, it is possible to download the images from Met's website and zoom in on them for a closer look.

Orthodox Christianity

Although ethnically and religiously diverse, the official religion of the Byzantine Empire was Christianity. Due to theological controversies mainly over the definition of the person of Christ as having two natures - human and divine- the Byzantine Christian community was divided into separate hierarchies. It is even suggested that the efforts to enforce loyalty to the Orthodox faith after the Council of Chalcedon in 451, which was met with resistance from Christian communities in the empire's southern provinces, may have been the cause of the not-so-hostile reception of the Arabs.2

|

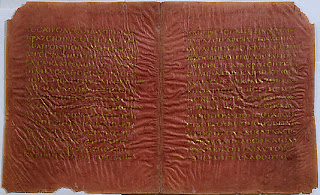

| Codex Sinopensis, 550-600 Made in Syria, Byzantine Palestine, Constantinople (?) |

"This sumptuous bifolium from a luxurious Gospel of Matthew, dyed in purple and illuminated in gold and silver Greek uncial (capital) script, reveals the highest level of Byzantine book production. The later appearance of similarly embellished Qur'ans, seen in the exhibitions final gallery, indicates that these standards transcended religious distinctions"

|

| The Attarouthi Treasure - Silver Dove, late 6th-early 7th century Byzantine Made in Attarouthi, Syria(Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

"The dove, with wings spread and feet tucked up as if in flight, represents the Holy Spirit that appeared above the head of Christ as he was baptized by Saint John the Forerunner (John 1:32). Early authors mention the presence of doves over altars in churches from Constantinople to Tours in France. This is the earliest known example of the type. Originally a small cross hung from the loop in its beak."

The Ivories of the So-Called Grado Chair

|

| Saint Peter Dictating the Gospel to Saint Mark, 440-670 (radiocarbon date 95% probability) Made in Eastern Mediterranean or Egypt (Victoria and Albert Museum) |

"The ivories from the So-called Grado Chair depict Saint Mark as founder and first bishop of the first church of Alexandria. The mixture of the Byzantine and Islamic elements in the decoration, especially in details of the cities, demonstrates the sophistication of ivory carvers in the eastern Mediterranean immediately before the body of the saint was transported to Venice. On this panel, Saint Peter (left), inspired by an angel, dictates his teachings to Saint Mark (right) in Rome. Saint Mark diligently records Saint Peter's words in a pose traditional for a scribe. Carbon- 14 dating of the fragment confirmed that the ivory dates within the time frame of the exhibition."

|

| Saint Mark Healing Anianos |

|

| Annunciation to the Virgin |

|

| Saint Mark Consecrating Anianos |

"The original use and the arrangement of these fourteen ivories of the So-Called Grado Chair with scenes from the life of Christ, depictions of saints, and of Saint Mark as first bishop of Alexandria remain uncertain. They may have been part of a liturgical throne given by Emperor Heraclius (r. 610-41) to Grado, Italy, after his successful re-conquest of Egypt..."

Syriac Christianity

The Syriac Church, among the earliest-established Christian churches had its roots in Antioch (Antakya), where the apostle Peter established a church in the first century. Although Greek was the official and elite language of Antioch, the working language of the region was Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic. 3

|

| Rabbula Gospels, Completed 586 Made in Syria (?) (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence) |

|

| Rabbula Gospels, Completed 586 Made in Syria (?) (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence) |

"The Rabbula Gospels represent the artistic prowess of the Syriac Church. Elaborate arcades frame the Cannon Tables that show parallels between Gospel passages. Among the images on these pages are King David with his lyre, the Nativity, and the Wedding at Cana witnessed by the Virgin and Christ."Notice how the arcades are very similar to the arches above the heads of the figures in the silver plates above, made in Constantinople depicting the scenes from the life of David. Another fascinating point mentioned in the audio guide was that according to recent discoveries, there was major repainting done on the manuscripts to moderate Christ's more "Syrian" features to have a shorter beard and reddish hair.

|

| Pauline Epistles from the Peshitta, 622 Made in Syria (The British Library) |

" The Peshitta, meaning "simple" or "common," is the Syrian version of the Bible. The text of this manuscript is written in a Syriac script called estrangela, that reads from right to left, as do Hebrew and Arabic."

Coptic Christianity

Traditionally, Saint Mark the Evangelist, the first patriarch of Alexandria, is accepted as the first patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt. The Egyptian language written with modified Greek letters, Coptic,used for liturgical and administrative purposes along with Greek was the primary language of the Church until the tenth century.4 The importance of Monasticism to Egyptian Christianity is affirmed in the artifacts present in this exhibition; especially magnificent is the Red Monastery which can be seen on a video in one of the galleries.

|

| Stele of Apa Shenoute, 5th-6th century, Made in Egypt |

"Apa Shenoute (346/47- 465) was among the most dynamic religious figures in late antique Egypt. Recruited as abbot (apa) of the White Monastery in Sohag when the community included only a few dozen elderly monks, Shenoute oversaw the monastery's expansion to a population of more than three thousand. He provided a model for monastic communities in Egypt through his reforms and writings and remains a popular figure in the Coptic Church today. The bearded figure, identified in Coptic as "Apa [Father] Shenoute," may commemorate the saint of perhaps a monk sharing his illustrious name."

|

| Manuscript Folios, Isaiah 12:2 - 13:12, 8th -9th century Made in Egypt, White Monastery |

"These folios are written in archaizing biblical style in the Sahidic dialect of Coptic, which was spoken by Shenoute, the leader of the White Monastery Federation. The use of expensive parchment rather than less costly paper attests to the White Monastery's thriving scriptorium and grand library."

Pair of Lithrugical Fans "Rhipidia"

11th -12th century,

Made in Egypt

"Deacons waved pairs of rhipidia to protect the bread and wine during the Eucharist. They came to symbolize the six-winged seraphim thought to be present during the service. As demonstrated by these fans, iconography originating in the early Byzantine period persisted into the Islamic era.

Each fan is surrounded by a quotation written in Greek using Coptic letters, from the Eucharist prayer of Saint Gregory. A later inscription "The holy Philotheos," likely refers to the patron of the church that owned the rhipidia. Each fan is decorated with beasts in the book of Revelation: the heads of an ox and a lion on one and the head of an eagle and an angel on the other. Each creature has six wings like seraphim. The decoration and the inscription reflect the symbolic role of the rhipidia in the lithurgy."

Judaism

The diversity of Byzantine Empire's southern provinces is further explored in the archaeological evidence from the indigenous Jewish communities' mosaics, inscriptions and texts written in Latin, Greek, Jewish Aramaic, Hebrew and Arabic. Some of the most fascinating objects on display are the documents from the 'Cairo Genizah,' the suppository of documents for the Jewish community of Ben Ezra Synagogue. 5 There is a video of a lively lecture given by Professor Steven Fine of Yeshiva University, about two of the objects on display at the exhibit, as part of the "Sundays at the Met" series that expands on the discovery and the contents of the "Cairo Geniza."

|

| Palimpsest of the Hebrew Liturgical Poet Yannai over Aquila's Greek Translation of 2 Kings 23:11-27 5th-6th century; overtext: 9th-10th century Made in Egypt of Palestine (?), from the Cairo Genizah |

"Documents preserved in the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat, Egypt (882), provide a rich account of Jewish life, liturgy, and religion in the early Islamic world. The Genizah testifies to the shift from Greek to Arabic, the adoption of the codex form, and the development of new forms of calligraphy and textual/critical apparatus by Jews during this period. The Cambridge scholar Solom Schechter discovered the documents in 1896.

This fragment from the Cairo Genizah originally contained portions of the Greek translation of the Torah by Aquila, a second-century student of Rabbi Akiba. In the ninth century, the Greek text was scraped off and replaced with Hebrew liturgical poems by the sixth-century Palestinian poet Yannai."

|

| Mosaic with Menorah, 6th century |

|

| Mosaic with Menorah with Lulav and Ethrog, 6th century |

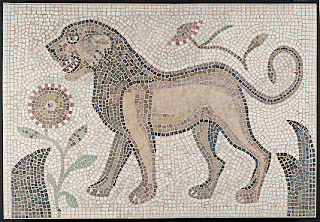

"The Hammam Lif Synagogue

A large mosaic found at the Tunisian town of Hammam Lif is so closely aligned with regional conventions that its structure was first identified as a Byzantine church. The presence of a Latin dedicatory inscription identifying the site as "Sancta Sinagoga" (Holly Sinagogue), flanked by two Menorahs, revealed that it was a synagogue. The floor consisted of four mosaic carpets, integrating distinctly Jewish symbolism with popular motifs of the period, including a lion. The Menorah was the primary symbol of Judaism in late antique and early Islamic worlds and is represented here in a manner that resembles depictions in synagogue mosaics and on liturgical objects from the Byzantine sphere. The two menorah panels flanked the Latin inscription on the synagogue's floor."

Pilgrimage

Holy sites commemorating the life of Christ, sacred places, and people of the Bible, and tombs of martyrs and saints were spread across Byzantium's southern provinces. Pilgrims believing that the power of a holy person, a holy object (relic) or location could be transferred thorough contact, traveled to these sites and to monastic communities and ascetics. 6 In this section of the exhibition a very impressive mosaic excavated from a church near the Holy Lands which has inscriptions in both Arabic (or Aramaic) and Greek is displayed.

There is a three hour video of the Symposium that took place at the Met in conjunction with this exhibition in which renowned scholars present their latest discoveries in their respective fields. Gabriele Mietke, Curator of Byzantine art from the Bode Museum, talks about dedicatory images and inscriptions on floor mosaics in the Heartland and the Southern Periphery of the Byzantine Empire. In regards to the Fieschi Morgan reliquary below, Chester Dale Fellow, Annie Labatt, gives a very interesting presentation regarding the transmission of iconography in a Pan-Mediterranean culture.

|

| Mosaic Fragment with a Pair of Goats, ca. 535/536, Made in Jordan, excavated at Khirbat al-Mukhayyat |

"Flanking the elaborate the palm tree at center are a pair of goats, doves, stylized plants, and two inscriptions. One is possibly the earliest inscription in Arabic ("in peace") in a church. It may also be in Aramaic ("Give repose [and] give salvation"). The other is the Greek name "Saola," probably referring to the archdeacon Saolos, whose name appears in two more inscriptions at the site. The bilingual character of the inscription reflects the multiplicity of the peoples living in Byzantium's southern provinces at the time."

|

| The Fieschi Morgan Staurohteke, early 9th century Made in Constantinople (?) |

|

| Back of the lid |

|

| Hexagonal Bottle with Stylite mid 5th-7th century Made is Syria (?) |

|

| Jug with Stylite 5th-7th century Made in Syria (?) |

|

| Pilgrim Token with Image of Saint Symeon Stylites the Younger 10th-11th century Made in Syria |

"Stylites were ascetics who lived on platforms atop columns. This movement had practitioners into the nineteenth century, from Mosul in today's northern Iraq to Gaul in France. Syria was home to large numbers of stylites, including the first stylite, Symeon Stylites the Elder (ca. 389-459)... Symeon the Elder used oil, water, dust and hnana (a combination of the three) in his miracles. Pilgrims may have collected these substances in bottles."

Iconoclasm

The iconoclastic controversy(726-74, 813-42), a century-long debate over the veneration of religious imagery began during the reign of the Byzantine emperor Leo III (r. 717-41). Confined mostly in Constantinople and its environs, there seems to have been a debate over the use of figural imagery in Byzantium's recently lost southern provinces. 7 Robert Edwin Schick, Research Fellow at American Center of Oriental Research in Jordan, talks about the destruction or alteration of images in eighth-century Palestine as the first speaker in the Symposium held at the Metropolitan Museum. Although there still does not seem to be a clear answer to why this was done, looking at the scrambled images, transformed into plants or other abstract designs in some cases, brings about a real sense of the people who lived thirteen centuries ago.

|

| Mosaic Depicting Nikopolis Set over and Altered Animal 719-720 and later Made in Jordan, excavated Church on the Acropolis, Ma'in |

Commerce

Trade routes extended throughout Byzantium's southern provinces carrying rare goods, and daily necessities throughout the region and across the Mediterranean. Silks and spices from the Far East... traveled up the Red Sea, past Mecca and Medina to Alexandria... and then north by land and sea to Constantinople. 8

This section of the exhibition has a display case of coins that start with Byzantine coins with Christian and Imperial imagery, then continues to imitative coins minted by the Umayyads as well as Sasanian Type Dirham combining Zoroastorian imagery with Arabic inscription to finally the Aniconic Dinar. It is a spectacular way of observing how rulers and people both can become amendable to the needs of changing times.

|

| Follis of Phocas (Focas) 609/610 Made in Antioch copper |

"The Byzantine Empire issued the gold solidus or nomisma, used primarily for large transactions such as tax payments, and several denominations of copper coins, the money of daily business transactions. Mints in Antioch and Alexandria supplied the majority of the coinage circulated in the southern provinces. The newly established Arab government inherited an efficient monetary system and made few changes during its first decades. The earliest Islamic coins derive from Byzantine coinage, most frequently that of the early seventh century. The caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685-705) introduced several issues of Islamic coinage. The Byzantine empire produced large quantities of copper coins. In Greater Syria, the forty-nummus (M), known as a follis, was the most common."

Byzantine

|

| Solidus of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine 629-31 Made in Contantinople Byzantine "Our Lords Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine Perpetual Augusti" |

|

| "Victory of the Emperors, fine gold, Constantinople" |

Early Islamic Coins

|

| Imitative Solidus of Byzantine Type ca. 660 Made in Damascus or Jerusalem |

|

| Dinar of Arab Type 694/695 Made in. probably Damascus Gold |

" Beginning in the 690's Abd al-Malik (685-705) issued a series of coins depicting a standing caliph. Although the rare precious-metal coins do not bear a mint-mark, they were presumably struck in Damascus. The copper coins were issued at sixteen mints. This is the final Umayyad series of coins to depict a human image. Loosely based on Byzantine coinage, the gold issues replace the figure of the Byzantine emperor with that of the bearded caliph wearing an Arab headdress, possibly a kaffiya, a long robe, and a sword grit around his waist. The shahada, written in Arabic, circles the observe."

" Beginning in the 690's Abd al-Malik (685-705) issued a series of coins depicting a standing caliph. Although the rare precious-metal coins do not bear a mint-mark, they were presumably struck in Damascus. The copper coins were issued at sixteen mints. This is the final Umayyad series of coins to depict a human image. Loosely based on Byzantine coinage, the gold issues replace the figure of the Byzantine emperor with that of the bearded caliph wearing an Arab headdress, possibly a kaffiya, a long robe, and a sword grit around his waist. The shahada, written in Arabic, circles the observe." |

| Dirham of Sasanian Type 693/694 Made in Damascus Silver |

"The caliph Abd al-Malik(r. 685-705) instituted significant change in coinage. His early issues struck in gold, silver, and copper replaced the image of the emperor with that of the caliph, removed the Christian cross, and used religious inscriptions, such as the shahada, the profession of faith.

The Byzantine emperor did not issue silver coins. This example modeled on the Sasanian drachma of Khusrau II, retains the sovereign's portrait and the Zoroastrian fire altar and adds the shahada in Arabic on the observe. Unlike Abd al-Malik's gold and copper coins, this coin bears the mint and the year on the reverse."

| Anonymous Aniconic Dinar 698/699 Made in, probably Damascus Gold |

"In 696/97 Abd al-Malik began issuing a series of coins bearing only religious inscriptions in Arabic. Such epigraphic coins are one of the many reforms introduced during his caliphate that laid the foundations for the imagery of the Islamic state.The design of Abd al-Malik's gold and silver coins- several lines of horizontal inscription enclosed by a circular marginal inscription- became the standard for precious-metal coinage for centuries. This example combines the shahada with two verses from the Qur'an."

Silks

Silk, a luxury good reserved for the wealthiest members of society, possessed a shimmering, light-reflecting surface so admired that it was called "the work of angels." Purple silk was popular among the elite, and the rarest purple was restricted for imperial use. Many silks were made in relatively simple lattice patterns. Finer ones, possibly woven at Panopolis (Akhmim) in Egypt, displayed detailed, animated figures from classical mythology often worked in two colors... Patterns popular during the Byzantine era remained in use in the early Islamic period, as proven by scientific tests such as Carbon-14 dating. 9

|

| Annunciation, 8th-9th century Made in, Alexandria or Egypt, Syria, Constantinople (?) |

"With its complexly woven design and elaborately varied color scheme, this fragment epitomizes the highest achievements of Byzantine silk production. The skillful rendering of the angel Gabriel and the seated Virgin as well as the attention to the ornamental motifs attest to the weaver’s skill. Such high-end silks were often sent as imperial gifts to neighboring courts. This work is thought to have entered the Vatican soon after its production; it was discovered in the twentieth century wrapped around a relic in a silver casket."The floral motifs between the roundels especially caught my attention due to their resemblance to the motifs in Islamic art; the tulip motif which is visible at the top of the picture, looks almost identical to those that can be found in Iznik tiles from several centuries later.

|

| Roundel with Amazons 7th-9th century (?) Made in Egypt or Syria (?) |

"Nineteenth-century excavations at the cemetery at Panopolis (Akhmim), a city long associated with Dionysos, yielded silks elaborately woven with classical motifs. Recent radiocarbon dating of textiles associated with the site place them between the seventh and ninth centuries, providing a sense of the continuity of styles as the region transitioned from Byzantine to Islamic rule.

Riding Amazons with one breast exposed represent another antique motif popular in the Byzantine and Islamic periods. Textiles with this pattern are traditionally associated with Akhmim."

|

| Pattern Sheet with Diaper Design 5th-6th century Made in Egypt |

"Silks were woven in many designs. One widely popular type was a diaper pattern that used a latticelike organizational scheme with narrow intersecting diagonal bands to create rhomboid or square fields filled with various motifs.The diaper pattern on this papyrus fragment, a pattern sheet for the woven decoration of a tunic, is similar to contemporary Persian silks. The dissemination of papyrus templates such as this and the textiles based on them perhaps contributed to the spread of Persian motifs in other media, such as mosaics."

Dress

Both Roman-style tunics and Central Asian–inspired tailored garments were worn in Byzantium's southern provinces from late antiquity into the early Islamic era, as proven by scientific testing of burial finds. During the Byzantine and early Islamic periods, tunics of brightly colored fabrics, with separately woven and applied elaborate decorative elements, were widely popular. Over time, the styles mingled, producing increasingly colorful decoration and elaborate ornament.10

There is a visual progression between galleries, from Silks to Dress where the patterns of fragments in Silks can be found on the examples of dresses displayed in this gallery and the textile fragments of wall hangings depict figures in these types of dress.

|

| Fragments of a Wall Hanging with Figures in Elaborate Dress 5th-7th century Made in Egypt |

Trade Goods

This gallery is an eclectic mix of objects that further emphasizes the use of similar motifs on different objects throughout the southern provinces.

|

| Pair of Earrings with Birds 7th-8th century Made in Egypt or Syria |

"New methods of crafting jewelry became popular during the early Islamic period, transforming the aesthetics of personal adornment. These crescent-shaped earrings display confronted birds—by now, three-dimensional in shape. The preference for filigree and wire decoration results in sophisticated, intricate designs visually distinct from Byzantine traditions."

|

| Plaque Decorated with Vine Scroll and a Bird, 8th century Maid in Egypt or Syria |

"Carvings on ivory or bone were often used in the eastern Mediterranean as attachments for furniture and other objects. These plaques, which vary in style, reflect the continuation of Byzantine vine patterns into the early Islamic era. Most are carved on a vertical axis and are at times inhabited by animals. On this plaque, a small bird inhabits the tree at lower left."

|

| Flask with Green Cameo 9th-10th century Made in, probably Iran |

"Animals—a popular theme during the Byzantine era—continued to appear in early Islamic art. Hares represented plenty and the hunt, a popular activity of the elite for centuries.

Cameo glass, widespread throughout the eastern Mediterranean in Roman times, was revived during the Islamic period. Here, the harelike figure is carved from a patch of green glass applied over the translucent glass of the vessel’s body."

|

| Eagle Censer 8th-9th century Made in Eastern Mediterranean |

"Three related incense burners (in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Malcove Collection, University of Toronto Art Centre, University of Toronto, and Musée du Louvre, Département des Antiquités Égyptiennes, Paris) with ornate domed lids are covered with openwork foliate decoration. Created centuries apart, they illustrate a common domestic object gradually evolving under Byzantine and Islamic rule. Their decoration evokes plenty, the triumph of good over evil, and the promise of eternal life—ideas that occur frequently in the art and inscriptions of the Byzantine and the Islamic worlds.This censer, covered with a vine scroll, has an eagle with a snake in its beak as a finial. Possibly symbolizing the triumph of good over evil, the motif and the vine scrolls are drawn from the Byzantine tradition. Islamic influence is evident primarily in its construction from a flat sheet of metal."

Palaces and Princely Life

With the arrival of the Umayyads in Byzantium's southern provinces, the artistic traditions of the region began to be transformed by their taste. The transformation, which extended over centuries, included both the survival of existing concepts and the creation of new ones. The first generation of Umayyad rulers built palaces along the border between the cultivated lands and the desert. Originally located on intensely irrigated and richly green sites, these palaces survive now largely as desert locations.11

On the Metropolitan Museum's Symposium video, Claus-Peter Haase, the Director Emeritus of the Museum of Islamic art, discusses New interpretations of the Enterance Facade at Qasr al-Mshatta in Jordan. Professor Haase also draws attention to the arcades that are present in a wide variety of mediums from mosaics to textiles to architectural facade decorations.

|

| Fragment Carved with a Rosette mid-8th century Made in Jordan, Qasr al-Mshatta |

.jpg) |

| Mshatta facade in the Pergamon museum in Berlin |

"Qasr al-Mshatta

The unfinished palace at Mshatta near Amman, Jordan is the largest of the Umayyad palaces. Resembling a fortress with its twenty-five semicircular towers and monumental entrance gate, it had a grand audience hall on the same axis as the entrance. The gatehouse complex near the entrance included a mosque. The exterior walls flanking the entrance gate were covered with elaborately carved decoration in the Byzantine tradition. The building may have been ordered by the Umayyad caliph al-Walid II (r. 743–44) to welcome those returning from the pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca and then left unfinished at his death.This torso is the remains of a large female figure, perhaps a dancer. Wearing revealing drapery and holding what may be a piece of fruit before her navel, she resembles the maenads—members of Dionysos’ retinue in the classical and Byzantine periods. She is one of a group of nearly lifesize male and female figures that decorated the audience hall of the qasr (palace)...

This luxuriantly foliate half of a six-lobed rosette once decorated the exterior of the walls encircling the palace. Rosettes were placed centrally in each of the monumental triangles that defined the surface decoration on the facade. The rosettes were carved from two stone blocks that were then joined horizontally."

|

| Brazier, 8th century (modern reproduction) Made in Eastern Mediterranean, excavated at al-Fudayn (Mafraq) |

"Al-Fudayn, an Umayyad residence located on trade routes joining cities such as Gerasa (Jerash) with the Arabian Peninsula, belonged to the exceptionally wealthy great grandson of the third Orthodox caliph ‘Uthman ibin ‘Afan. It was destroyed in the early ninth century, when a subsequent owner opposed the Abbasids. These luxury goods were found together and were perhaps hidden at that time.Dionysiac scenes appear under the arcades on this brazier. The erotic cavorting maenads, satyrs, intimate couples, and Pan suggest the brazier may have been used in the bathhouse excavated at the Umayyad palace. This modern reconstruction is based on the seven pieces of the original found in a hoard long hidden at the site."

|

| Ewer signed by Ibn Yazid 688/689 or 783/784 or 882/883 Made in Iraq |

"This elegantly shaped metal ewer is an everyday object transformed into a sophisticated work of art. The Arabic inscription in Kufic script around the rim identifies the artist: "Blessings to he who fashioned it, Ibn Yazid, part of what was made at Basra in the year sixty-nine." The vessel combines Byzantine-inspired surface decorations with a pear-shaped body, long neck, high-flaring foot, and half-palmette-shaped handle related to post-Sasanian metalwork. The ewer’s heavy form and the faceting on its body and neck suggest a late eighth- or ninth-century date."

|

| Luster-Painted Flask 8th-9th century Made in, probably Egypt |

|

| Luster-Painted Bottle 8th-9th century Made in Syria |

"Vegetal motifs drawing upon Byzantine and Sasanian forms developed in the arts of the Umayyad and early Abbasid period in the territories, once the southern provinces of the Byzantine Empire. Based on these traditions, the abstract forms and styles of ornament that subsequently developed at the Abbasid capital at Samarra would have a profound impact on the art and architecture of the Islamic world.(L) Originating in more realistic Byzantine vine patterns, the graceful vines and handsomely drawn leaves on this flask are rendered flatly with no attempts at naturalism. The arrangement of the vines and leaves enhances the shape of the flask.

(R) The alternating gold palmettes and leaves around the body of this bottle are worked in a technique popular in the Roman period. The gold foil is sandwiched between two layers of glass. The blue dots may relate to dots in Qur’ans."

|

| Luster-Painted Bowl 9th-10th century Made in Iraq |

"In the ninth and tenth centuries, Islamic potters adapted to ceramics the luster decorating technique known to pre-Islamic glassmakers in Egypt. Here the decoration displays a two-dimensional version of Samarran-style vegetal decoration that can also be interpreted as a pair of confronted, stylized birds with leaf-shaped beaks."

|

| Dish with Molded Kufic Inscription 9th century Made in Iraq |

"The angular Kufic inscription, "Patience is the key to victory. Blessing," decorates this bowl. Reinforcing the maxim, the words "patience" and "victory" are highlighted in green and/or filled with dots. The yellow and green color scheme recalls Chinese Tang dynasty (618–906) pottery, which was prized at the Abbasid court."

|

| Pair of Doors with Carved Decoration second half of the 8th century Made in, probably Iraq |

"Richly patterned like the stone carvings at the Umayyad palace at Mshatta, these doors are said to have been found near the Abbasid capital Baghdad in Iraq. With their distinctive mixture of naturalism, abstraction, and geometry, they epitomize the transitional style characteristic of the late Umayyad and early Abbasid periods. Taste for surface pattern and stylization spread widely at this time, appearing in monuments throughout the Islamic empire from Central Asia to North Africa, including the lost southern provinces of the Byzantine Empire."

Islamic Religious Works

The Qur’an, the religious text central to Islam, is a series of revelations from God transmitted by the angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad in Mecca and Medina between about 610 and the Prophet's death in 632. During the rise of the Umayyads and the transition of rule in the eastern Mediterranean, the text of the Qur’an, originally recited from memory, came to be written in Arabic, inspiring not only religious devotion but also the creativity of craftsmen. Elaborately worked verses from the Qur’an became standard decoration for mosques, funerary monuments, and other works. Calligraphy as it evolved to present the teachings of the Qur’an became a major artistic tradition of the Islamic world. Mosques were erected in cities now under Muslim rule. The most important were the Friday mosques built to hold all the faithful for prayer and also functioned as evidence of the authority of the ruler. Byzantine artisans may have done the elaborate mosaic decoration of the Great Mosque in Damascus, the Umayyad capital, built between 705 and 715. In Egypt in the ninth century, as Ibn Tulun (r. 868–84) established his quasi-independent state, he would model his great mosque on the one in the Abbasid capital at Samarra.12 |

| Folio from Qur'an late 8th century Made in Syria, Damascus |

"The elegant Kufic script on theis folio from a Qur’an attributed to the Umayyad capital is written in the horizontal format that became standard for Qur’ans. Round markers in gold indicate groups of ten verses for recitation, while red dots provide vocalizations to clarify meaning. The elegance of the Kufic calligraphy, which carries the eye easily from right to left across the page, is apt for folios containing the sura Al-Zukhruf ("Ornaments of Gold"), which asserts the centrality of Arabic as the heard and written word of the Qur’an. A second folios from this Qur’an in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum, New York, is included in the exhibition."

|

| Folio from a Qur'an ca. 900-950 Made in, Probably Tunisia, Qairawan |

" Few objects demonstrate the inventiveness of early Islamic artists as elegantly as the now-dispersed Blue Qur’an. The manuscript reflects an awareness of Byzantine purple-dyed luxury manuscripts written in gold and silver. The later Muslim scribes’ innovations, however, are evident in the manuscript’s horizontal format, indigo-dyed blue parchment, and golden Kufic script. The combination gold and blue may have carried heavenly associations, as the same color scheme was used in the Qur’anic inscriptions in the Dome of the Rock dating to roughly the same period. "

|

| Portable Mihrab 10th century Made in Egypt |

"Mihrabs are the focal point on the main prayer wall of mosques, directing the prayers of the faithful toward Mecca. Usually they are adorned with Qur’anic verses and patterns related to other decorations in the mosque. This small portable mihrab is inscribed with the names of members of the Prophet Muhammad’s family and of some of the subsequent Shi‘ite imams (leaders), indicating that the owner was a Shi‘ite Muslim. It was used for prayers while traveling or placed under the head of the deceased according to Shi‘ite tradition."

Metropolitan Museum of Art has a feature on their website called "MY MET" where participants can share their experience of the museum using their favorite works of art from their collection. I want to finish this little tour of an amazing exhibition by saying "MY MET... MY SCHOOL, MY HOME, MY HERITAGE"

References

1 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition introduction

2 Hugh Kennedy. The Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East. Aldershot, 2006. pp. 141-83

3 Nancy Khalek. "The Syriac Church." Byzantium and Islam:Age of Transition, 7th-9th Century.New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012. pp. 66

4 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Coptic Christianity introduction

5 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Judaism introduction

6 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Pilgrimage introduction

7 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Iconoclasm introduction

8 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Commerce introduction

9 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Silks introduction

10 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Dress introduction

11 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Palaces and Princely Life introduction

12 Metropolitan Museum of Art Website, Byzantium and Islam exhibition, Islamic Religious Works introduction

.JPG)

Thank you for this stunning review Sedef. Looks like an absolutely wonderful exhibition. Your having that personal experience and connection the subject matter makes it all the more engaging to read.

ReplyDeleteIt's so wonderful to have such things accessible online for all to enjoy and learn from.

Many Kind Regards

H

Hasan,

DeleteI am glad I could share my experience and excitement about this wonderful exhibition that opened my eyes to a whole new world. Met did an exceptional job with this exhibit because for the first time the information and the visuals on their website seems to be geared towards education not just attracting visitors. The lectures and the blog are also extremely helpful.

Thanks for your kind words

Thanks for this, Sedef! I've been wondering about this exhibit -- it seems like such a great (and huge) topic, and I'm so glad that you feel that they covered it well. The silver plates from Constantinople are amazing! And I didn't know that the palace at Mshatta may have been built to welcome people returning from the hajj -- fascinating! You've also made me see coins in a completely different way -- I've never been that interested in them, but I am very interested in cross-cultural connections and exchange, and although I feel a bit silly about it now, I'd never thought of coins in that context. So thank you! Can't wait to check out the info and videos on the Met website.

ReplyDeleteTake care --

-Karen

Many thanks, Sedef - and congratulations on a fascinating post! I am now sorrier than ever to be missing this show. Fortunately, I was in New York just after the opening of the reinstalled Islamic galleries and saw that they did a wonderful job of presenting emerging patterns of style and influence - so, they are certainly the right people to have realized this particular show.

ReplyDeleteThank you for taking the time to comment. Working on this post was a valuable experience in and of itself but to receive such positive feedback is priceless.

ReplyDeleteKaren, this was the first time I realized that coins could relate to us the same kind of stories that other artifacts tell us - of the people who have lived and their way of life. What was especially important for me personally was that not only did I get a glimpse of how it might have been so long ago, but also I found a common link to my own culture in these objects.

Dr. Goldberg, the Islamic galleries are impressive which I reviewed here as well as one of the lectures given in conjunction with the exhibit on Luxury Arts and the Art of the Book by Professor Jerrilyn Dodds. What is so wonderful about the Met is the accessibility of such events to the general public. Now with a blog and so much more information on their website, they seem to be making a big effort to keep up with the times which I find admirable.

Thanks again for the encouragement...