|

| Square emerald aigrette, TSM 2/313, 18th century (Topkapi Palace Musem) |

"Made up of the glories of the most precious gems, to describe them is a matter of inexpressible difficulty. For there is amongst them the gentler fire of the ruby, there is the rich purple of the amethyst, there is the sea-green of the emerald, and all shining together in an indescribable union. Others, by an excessive heightening of their hues equal all the colours of the painter, others the flame of burning brimstone, or of a fire quickened by oil."

~ Pliny the Elder (describing opals)

From philosopher to the ordinary woman/man for centuries jewels have been a source of fascination; their natural brilliance, vibrant colors and expressiveness have been compared to all the wonders of the universe. But jewelry, as part of the persona of a sovereign has greater connotations than mere beauty or worth - it becomes a symbol of imperial magnificence portraying their might and refinement concurrently. When the sovereign in question is the Ottoman Sultan these symbols take on a more exotic, intriguing configuration that may need further elucidation. During a talk about her latest book, Imperial Ottoman Jewellery: Reading History Through Jewellery, Prof. Dr. Gul Irepoglu provided some enlightening facts as well as stunning visuals of the jewelry of the Ottoman Sultans. One of the most interesting parts of her talk was the inclusion of miniatures, which are considered to be historical documents, to highlight where and how these jewels were utilized.

|

| Suleiman the Magnificent's Throne, 16th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

Dr Irepoglu's opening remarks about the relationship of the Ottomans with their treasures as objects to be surrounded by and utilized in their daily lives as opposed to being hoarded foreshadowed the direction of her talk. She started with some of the most impressive pieces of the Topkapi treasury department, the variety of different thrones. These, according to Irepoglu, also reflect the typical characteristics of the time they were made containing within them the keys to the beliefs of the day. In regards to the sixteenth-century walnut throne from the earlier part of Suleiman the Magnificent's reign, while it is easy to recognize the austere beauty of the ebony and mother-of-pearl inlays, Irepoglu pointed out the turquoise stone in the middle of the back of the throne that is not so easily discernible. This, she interpreted as being utilized for its supposed protective attributes. Turquoise was believed to have properties to induce invincibility, deflect wrath, keep poverty and nightmares at bay, protect from natural disasters, give joy, happiness and strength, be good for the eyes, cure poisoning and survive accidents as well as increase lifespan.1

|

| Nakkas Osman, Selim II Enthroned, 1568 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Sedefkar Mehmet Aga, Sultan Ahmed I Throne, 17th c (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

The throne belonging to Sultan Ahmed I is quite entrancing not only for it's exquisite decoration but also for its architectural quality. Built by the architect of the famous Blue Mosque, Sedefkar (mother-of-pearl-inlayer) Mehmet Aga, the 17th century throne inlaid with tortoise and mother-of-pearls, laden with turquoise, rubies and peridots, according to Irepoglu defines the predominant taste of this century. The profusion of flowers - carnations, tulips and undulating vegetal motifs are likened to the naturalistic sixteenth-century depictions on paper of flowers by Karamemi or Iznik tiles from the Selimiye Mosque by Irepoglu. Besides the emerald and gold pendant that hangs down the middle of the dome, there is another feature of this throne that deserves further investigation - a clock case in the form of a lantern at the very top of the dome. This unique feature is explored by Irepoglu in the book by considering it's "hexagonal body topped with a cupola, in the late Renaissance style" and ruminating whether it was one of the gifts Queen Elizabeth I sent to Mehmet III in 1599 or if it was the artist's allusion to European art. Whichever it is, I am grateful to Dr Irepoglu for pointing it out, since there was no other way we could have been privy to this feature.

While their fathers graced golden thrones embellished with precious gems, the newborn Sultans (princesses) or Sehzades (crown princes) born in the harem, would also receive precious cradles that would be accompanied with gemstone embellished quilt and blankets from the steward of the treasury as well as other members of the court. The imperial gifts from the Queen mother and the grand vizier were supposed to arrive by a stately procession. If the newborn was a prince an aigrette was also supposed to be included in the gifts. 3 Aigrettes can be seen on the canopy of the four Shehzade's in the court artist Levni's album, Surname-i Vehbi, an album of the Circumcision Festival of Ahmed III four sons.

In the Eastern tradition the aigrette that the Sultans wore on their turbans were regarded as their crowns. The aigrette could be worn in several ways including upside down and up to three at a time (See Selim II Enthroned miniature above). Gul Irepoglu explains:

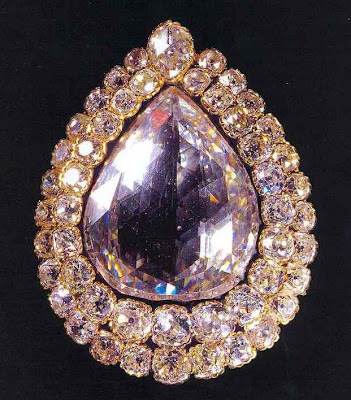

Spoonmaker's Diamond is a jewel that is supposed to have entered the treasury in the seventeenth-century but the rest of its history is surrounded by many myths and stories, none of which has been corroborated as the truth. For years everyone that visited the Topkapi Palace treasury would go to see this magnificent 86-carat diamond surrounded with a later addition of 49 brilliants nestled in its black velvet case, without having an inkling as to its purpose - it just seemed like a befitting jewel for the treasury of the Ottoman Sultans. One of the most exciting stories Dr Irepoglu shared during her talk was about how she discovered the true function of the Spoonmaker's Diamond when she was working as one of the curators of the exhibition The Sultan's Portrait in the Topkapi Palace. She says she noticed an oil painting in storage of Sultan Abdulhamid I with a diamond aigrette that looked very familiar. Since she was not able to handle the Spoonmakers Diamond herself, she inquired from a museum official if there was a sturdy pin on the bottom of the piece. As it turns out, there was a pin at the bottom which would confirm its function as an aigrette.

|

| 18th century Gold-Plated Walnut Cradle, (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Levni, Surname-i Vehbi, 175a-Sultan distributing Gold after the Circumcision,1727 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Detail showing each Shehzade lying in their individual tents that had their aigrettes above the entrance |

In the Eastern tradition the aigrette that the Sultans wore on their turbans were regarded as their crowns. The aigrette could be worn in several ways including upside down and up to three at a time (See Selim II Enthroned miniature above). Gul Irepoglu explains:

"An aigrette basically is a socket into which plumes or shorter feathers are fitted, the socket itself attached to a sturdy pin of nielloed gold, with additional reinforcements of hooked gold chains on either side. Plumes of cranes, peacocks, herons, hawks, ostriches, crested cranes or birds of paradise complete the jewel."4

|

| Sapphire Aigrette, 16th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Carnation Aigrette, 17th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

Aigrettes symbolizing the sovereignty for Ottoman sultans continued their ascendancy even after a Sultan passed away - according to Irepoglu the Sultan's aigrette would be placed on his casket at his funeral and later in his mausoleum. The carnation aigrette above is supposed to have come from the mausoleum of Sultan Ahmed I.

|

| Levni, Kebir Musavver Silsilename, Sultan Suleiman, 1710-20 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Levni, Kebir Musavver Silsilename, Sultan Ahmed III, 1710-20 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Equestrian Portrait of Sultan Murad IV, 1623-40 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Kasikci Diamond, 17th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Rafael, Sultan Mustafa III, 1775 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Osman II, 1618-22 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Tulip Stirrups, 17th century (Kremlin Palace Museum) |

It wasn't just the person of the sovereign that was adorned with jewels, his horse would also be elaborately embellished as well. In the miniature of Osman II, the horses tacks and stirrups are all gold decorated with precious stones. Irepoglu states that since the stirrups were at eye level of the spectators they were decorated heavily. The Tulip Stirrups from the Kremlin Palace Collection were a gift to the Russian Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich in the seventeenth-century. 5

|

| Sultan Abdulmecid, 1850-1859 (Pera Museum) |

|

| Jeweled rock crystal flask, (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Jade Tankard, 16th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

Sixteenth-century was the Golden Age of artistic creation in the Ottoman Empire. It was a time when the empire was at the height of its power and the colors in the illuminations being produced reflected the might of the empire. The trend for color of sixteenth-century extended to the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries.

The austere magnificence of the sixteenth-century became more ostentatious in the seventeenth-century and as the empire started to lose it's former strength, Irepoglu suggests they seem to have become more extravagant.

|

| Bosnian Master Mehmed, Divan binding, 1588 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

There is a saying "The Quran was revealed in Mecca, Recited in Egypt and Written in Istanbul" which highlights the importance given to the production of the Qur'an but calligraphy and illumination were not solely used for the Holy book. Regarding this binding made for the collection of poetry by Murad III, one can see the importance that the Ottoman Sultans impressed on the arts. Gul Irepoglu refers to this binding as illuminations turned jewelry.

|

| Gold Ceremonial Flask, 16th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

This gold ceremonial flask which is the same shape as the traditional leather water flasks , is on the cover of the book and by selecting this piece for the cover Dr Irepoglu explains she wants to emphasize traditions transcending centuries.

|

| Diamond Stands (for Turkish Coffee), 19th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Dagger with an Emerald Hilt, 1747 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

The jeweled dagger with its three cabochon emeralds, a tiny watch on its pommel and an enameled still life, according to Irepoglu, is the perfect embodiment of the eighteenth century refined taste as well as a reflection of the transition period of the Ottoman empire. This was commissioned by Sultan Mahmut I in 1747 as a diplomatic gift for Nadir Shah of Persia but when he was assassinated before the gifts could reach him, it was returned back to the Topkapi Palace.6

|

| Transylvanian Prince Istvan Bocskay's gold crown, 1605 (Weltliche Schatzkammer, Hofburg, Wien) |

|

| Bridal Headpin, 1875 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

| Necklace, 17th-18th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

|

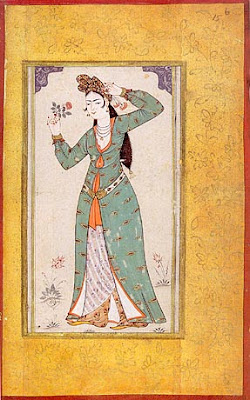

| Levni, Young Ottoman Lady, 18th century (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

The subject of jewelry, especially a treasury like the Ottoman Empire's that was never invaded and remained intact throughout the centuries is so vast that a mere blogpost can never do it justice. Imperial Ottoman Jewellery: Reading History Through Jewellery gives a comprehensive overview of the subject with unique inclusions and stunning photographs. It combines visual as well as literary sources, foreign travelers accounts to provide a framework of the impact the Ottoman Sultans made on observers. But the most refreshing aspect of the book and the talk was about the details that help to decipher the messages contained in these beautiful artifacts.

|

| Siblizade Ahmed, Sultan Mehmed II, 1480 (Topkapi Palace Museum) |

Resources

1 Gul Irepoglu, Imperial Ottoman Jewellery: Reading History Through Jewellery, Istanbul: Bilkent Kultur Girisimi Yayinlari, 2012, p. 66

2 Ibid., p. 102-103

3 Ibid, p. 143

4 Ibid., p. 194

5 Ibid., p. 179

6 Ibid., p. 158

7. Ibid., p. 318

8. Ibid., p. 282

www. artstor.org

Thank you for this Sedef! Prof. Irepoglu's book is a seminal publication, and who better than yourself to deliver this wonderful summary.

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading about the subjects covered in the book presented via the talk - as this invariably guides us to the elements of the topic which drove the author's passion to dedicate so much time and effort to its study.

I've always found aigrettes fascinating, and it was lovely to learn a bit more about them through this post!

Many thanks for your efforts, with each post I feel the symbolic distance between east and west slightly reduce. Bravo!

H

Great post! Thanks for highlighting all the decorative arts and non-traditional "jewelry" that the Ottoman court created. The treasures of the Topkapi Palace are fantastic.

ReplyDeleteHasan -

ReplyDeleteThanks, I enjoyed reviewing this talk almost as much as the talk and the book itself. Dr. Irepoglu definitely has a great passion for her subject matter and it was a delight to listen to her. I am glad you enjoyed reading about it.

The distance between east and west is for the most part a construct of another way of lifetime and I feel it's our job to bring awareness in regards to this. What better way than with art history?

Christina -

I just wish I could have included more... Topkapi is indeed magical and what we see is the tip of the iceberg... which is why Dr Irepoglu's book is so great -she has included objects that we don't see regularly on display.

Thank you for stopping by.

Fascinating, Sedef! I love that artisans left the jewels in their natural forms. And how interesting that this collection remained intact - of course it did, but I hadn't thought about what that might mean for history and art history. Thanks for another great post!

ReplyDeleteHi Karen, I have always loved the natural stones but had not considered the why of it. I am grateful to the historians and art historians whose work brings these details out. Thanks for the comment.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteI am continually amazed by the amount of information available on this subject. What you presented was well researched and well worded in order to get your stand on this across to all your readers.

ReplyDelete